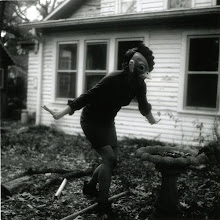

Fig. 12

There were no cars in Vinson Stag’s garage; only a white table with a shell reloader sitting in the center. When he was younger, Vinson would stand beside his father watching him reload shotgun shells for hours between beers and old country songs on the radio. The empty shells sat in metal army surplus boxes next to the legs of the chair, hollow greens and reds, their gold heads dull in the shadow of his father’s boots. As he selected a shell from the box he said, “Always remove the old primer and never have heat near this machine, understand?” Fitting the shell in the first slot, his father pulled hard on the lever and with a metallic crunch the tiny piece would fall into a small container of now inept metal bits. A new primer was placed into the machine and with another fall of the lever the head was restored. Vinson’s father grew his beard out when there was snow on the ground. When he hugged him at night, it smelled like cedar and gunpowder.

“When you put the powder in the shell, be sure not to spill it everywhere,” he said with another pull of the lever. The gunpowder hissed through the funnel and into the shell until the switch clicked and stopped the flow. After inserting a bright red piece of plastic into the shell, the machine rattled as the remainder of the case was filled with shot pellets. Tammy Wynette was moaning on the radio as the final lever pull sealed the shell and it was placed gingerly into another metal box.

Vinson received his first rifle at the age of ten and every gun owned by his father at the age of forty. They sat on the deer hoof gun racks in the back room, surrounded by turkey wings, various antlers, and taxidermy birds. There were photos of Vinson and his father on the plains with felled antelope or up to their waists in snow dangling limp pheasants from their gloved hands. Vinson never had the facial hair of his father in the pictures, just shallow peach fuzz on his upper lip.

He never married but chose to stay shut up in his cabin in Black Hills under the dull lamplight of a wagon wheel chandelier, drinking beer and black coffee. The cold winter air drifted between the floorboards from the basement where Vinson kept his extra freezer and worn table. At night he descended down the steps and pulled the chord of the light bulb that hung above the table before switching on the radio and sitting down. Using an electric sander, he careful traced over the edges of mount boards for trophy displays. The sawdust coated his pants and boots and fall to the floor, slowly changing their dark colors to lighter hues. Vinson typically used darker stains for the wood. The tips of his fingers were often dark brown with hints of yellow from chain smoking. He never smoked in his workshop because of the turpentine fumes.

A couple of days after the funeral, Vinson polished his father’s guns while listening to Tammy Wynette records and organizing ammunition into their appropriate boxes. He kept cleaning and rearranging manically for two days sporting dark circles around his eyes and the rough stubble of a much older man. The liver had gone first, then his heart begin to harden, and finally the black tar shellacking his lungs—that’s how his father went. Each organ ceasing one after the other in such efficient order that it reminded Vinson of cleaning an animal. “Always clean them carefully, Vince,” his father would say, “don’t just throw everything in a bucket and call it finished.” He could picture the hands of doctors taking apart his father piece by piece on the operating table and throwing them into a bright orange Home Depot bucket.

When his mother called the next day, Vinson was polishing his boots. Their conversation was short and practiced, a formality. No, he couldn’t visit this weekend, and yes he was doing fine, he didn’t need anything. Both of their voices were hollow and clipped, lost in the background static. The exchange began to drop off and was ended reluctantly even though nothing was said. His mother finally sighing, “You should really talk to someone…living up there alone.” After hanging up the phone, Vinson continued to polish his boots.

After his father died, Vinson could never bring himself to pick up the guns and go out hunting again. The waiting and watching and patience lost its appeal. He tried once, a month after. Picking up his shotgun he walked into the woods and waited atop a deer stand. The air was dry and the last leaves clung desperately to their branches and he waited. Squirrels dug through the layer of dead foliage on the ground while crows screeched on naked branches and Vinson thought of his father’s unblinking eyes scanning the tree line waiting for the pointed silhouette of a buck. The crunch of dead leaves brought him out of his nostalgia. With his head bowed to the ground, a large buck entered Vinson’s view. The animal was built but slender, fur matte in the light of dusk, the ten points of his rack seemingly growing from the forest floor. Vinson brought his scope to his eye and aimed for the vital spot below the shoulder. As the animal continued to nose through the leaves, he tightened his finger on the trigger following the deer’s motions with the end of his gun. Vinson remembered his father in the backyard carving into the body of a stag and gently placing the organs into a five-gallon bucket. The air smelled like musk and blood and the wide brown eye of the deer was glazed over, barely reflecting the light from the headlights of his father’s idling truck. Its tongue hung out of its open mouth accompanied by the sound of internal digging. The image of his father as a field guide illustration returned: arms held apart and the body splayed open, a caption below reading ‘Fig. 12-The Process of Gutting’.

Vinson stared at the animal in his scope as it quickly lifted its head, startled and ran into the forest. Only then did he notice his open mouth and wet cheeks. Salt and mucus were running down his face and hollow sobs echoed from his chest and through the trees. The crows had quieted and the forest was silent as he placed his gun in his lap, useless and impotent and cried into his gloved hands.

No comments:

Post a Comment