More than a month ago, I wrote this short story for the Memphis Magazine fiction contest. I haven't heard anything in a while, but it's about time I posted something.

More than a month ago, I wrote this short story for the Memphis Magazine fiction contest. I haven't heard anything in a while, but it's about time I posted something. For the fifteenth day in a row Beth awoke to the rustle and scraping under the floor. Carmine with his spoon, licking and smacking and gorging on the clay under the house. Before she ever had a chance to start breakfast he was pushing aside mothballs and exiling raccoons for his feast.

Standing in the middle of the kitchen, she listened while palming the eggs. Rolling the brown shells in her hand, she followed the wet drag of Carmine's utensil on earth, stepping quietly and standing above his head. Carmine with no facial hair for the clay to cling to. Carmine who filled the gaps of lost teeth with red dirt. Carmine with the guilty red hands.

Beth watched the egg whites spread and solidify as the front door flapped open and her son wiped his feet on the mat. "Morning," he said, sucking on his finger and wiping his free hand on his pants.

She turned slightly and nodded, eyes still fixed on the frying pan. Carmine pulled his chair across the floor and sat at the table. "No snakes under the house today. The mothballs must be scaring them off. Sure makes the house smell though."

With the heat came the serpents that coiled under the porch stairs, running from sun and anxious to surprise. When her husband was still around, each leaky pipe meant wrestling with the reptiles and the slim chance of wrangling them out of dark spaces in the house. They waited behind the icebox, between the wall and the bathtub, and once beneath their son's crib. After finding a large, black snake arranged on the floor beneath the sleeping baby, her husband bought mothballs and sprinkled them under the house. Not a snake since, but with every rise of the heat index, the fumes permeated the house. Even after the end of summer, the mothballs stayed, ammoniating Thanksgiving and Christmas.

"Why bother sitting at the table if you already filled up on dirt," Beth asked, scraping the eggs from the pan and onto a waiting plate.

"You're going to eat the foundation right out from under the house. One day we're going to wake up six feet in the ground, mud covering the windows and no way to get out the door."

Carmine swung his stained feet back and forth as he watched his mother pick at her breakfast. He glanced, uninterested, at her plate, then pushed his chair back from the table. "You don't have to be so mean, mama."

Her fork scraped against the plate, shrill and familiar. "Boys aren't meant to eat dirt. You're getting too old to make mudpies. Do the boys at your school do that? Push away their lunches and start tucking in the ground," her voice rising as she stabbed her eggs with the fork. "We're not poor. I cook you three meals a day and even then you sprinkle dirt on your plate."

"It tastes better," he mumbled, running his nail on the edge of the table top.

"The dirt under the house is the best dirt. I don't like other dirt that much."

Digging in his pocket, Carmine fingered a saved clod and resisting the urge of crumbling it over his mother's eggs when she had her back turned.

"I'm going to the river, mama. Going swimming."

He slid off the chair and started towards the door, looking over his shoulder at his mother. Beth stared back at him with sunken eyes and a hunched back. Every day she slumped forward further--he was waiting for her nose to touch the plate in front of her. He ended the image with the slam of the screen door.

Beth pushed her plate away and listened to the hot air move through the house. "He wouldn't be acting like this if you were still around," she said to the empty kitchen, "no, you would have already tanned his hide if he walked in here every day with dirt around his mouth."

She got up from her chair and began to clear the table. Beth examined the small potted herbs on the window sill and started filling a small cup with water. As she was pouring small amounts of water into the plants' pots, she noticed the bright orange smears leading from the door to the kitchen chairs. Cursing, Beth filled a bucket with soapy water. She kneeled on the floor and scrubbed the boards, soaking the hem of her skirt.

Carmine kicked up dust as he walked down the road. He stood with his head back and mouth open as if in a snowstorm as the sediment fell onto his waiting tongue. As he made his way down to the river, Carmine peeled his shirt off and tied it around his waist, scratching at the clay stains. The stains didn't budge and he decided to wait till he got to the water's edge to wash out his shirt.

When he reached the river, Baron was waiting for him. "I didn't think you would show up," Baron said, "I thought your mama might of made you stay home."

Baron sat on the low branch of a tree, already in his underwear and sweating. Carmine shook his head as he stripped off his pants and crouched in the water, rubbing his shirt against a rock. "Naw, she was mad but I left before she could do much."

Baron jumped from his branch into the water, splashing Carmine as he continued to scrub. When he was sure Baron wasn't looking, Carmine shoved a fistful of mud into his mouth. He rolled it around and sucked it down slowly. It felt good and cold as it slithered down his throat. Baron waded over to Carmine and pressed his finger hard against the boy's shoulder. "You're already pink, chief."

"Don't do that," he said, slapping away his hand. Baron splashed water in Carmine's face then swam back into the open water. He finished with his shirt and laid it over a shrub to dry. "Why don't you come out and swim?"

Carmine looked at Baron and clutched his stomach. "I got a stomach ache."

"Did you eat something bad?" Baron laughed and splashed in Carmine's direction. He replied by swatting water back at the boy and waded further from the shore. Baron disappeared under the surface laughing and Carmine vomited into the river.

Beth was sitting at the window with her chin in her hands when Carmine came home. His wet shirt was draped over his shoulder and he was holding his sunburned stomach as he walked up the steps. "I don't feel good, mama."

He stood before his mother and placed his head against her stomach. "My stomach hurts," he said, holding onto her hand. She looked at her son and placed her hand against his forehead.

"Well, you feel hot but that could be from being outside. Go lay down and I'll bring you some water. If you don't feel better by tonight, I'll call the doctor."

Carmine vomited for the rest of the day into his mother's mop pail. By evening, the doctor was beside Carmine's bed, holding his wrist and staring at his watch. "How long have you been feeling bad, son?"

"This morning when I went swimming. Came out of nowhere."

The doctor nodded and took out a thermometer. "Eat anything strange? Bad meat? Raw eggs? Anything like that?"

Carmine shook his head and looked at his mother. She furrowed her brow before saying, "Well, he's been eating dirt and mud for the past couple of weeks." The doctor looked at her, then at the boy.

"Is that so?"

Beth sat with the doctor at the kitchen table, holding a cold glass of water against her sweaty hands. "Where's he been eating dirt?"

"Under the house. Probably at the river, all over--I have no way of knowing."

The old man looked at her a moment while he readjusted the lapels of his jacket. "There are all kinds of things in mud, but what you have to worry about is parasites. Your boy's feeling sick because he's got a belly full of nematodes," he said, "It's nothing too serious. It's the same kind of worm a dog gets from eating scat. I'll give you some medicine that'll push them out of his system."

She stared at the doctor in disgust. Not only was the doctor's comparison of her son to a dog outrageous, but the idea that her son was full of worms turned her stomach. "I really appreciate you taking a look at my boy, but what I want to ask you is why is he eating dirt? It's just not right! It's not normal!"

"Now you don't need to get upset. It's not right but it's not unusual. There are lots of people who eat dirt. Sometimes your body is missing something that it needs, and sometimes that something is in the earth itself. A lot of the time, kids or pregnant women eat dirt for the iron. I even read a newspaper article that they've got a group of people in Tennessee that eat the clay right off the bluffs of the river. They bring buckets just to carry it home with them.", he explained.

Beth sat twitching in her chair, her hands upsetting the water in the glass.

"Don't look so worried, Beth, he'll grow out it sooner or later. I'll give you a prescription for some iron pills as well." He snapped his bag closed and stood to leave, briefly stopping beside Beth to place a hand on her trembling shoulder. "If you need anything else, give me a call. Here's the prescription. They should be able to fill it at the pharmacy." The door slammed, causing Beth to jump. She leaned her elbows on the table and quietly began to cry.

The next day, Beth dressed Carmine and led him to the front seat of the car. "Where are we going, mama," the boy croaked.

"We're just going into town to get you some medicine," she replied, shouldering her purse and wrestling with the car door. She started the car and poked Carmine, gesturing towards his seat belt. After he buckled himself in, Beth pulled out onto the dirt road and drove towards town. Carmine twisted the knobs on the radio, searching the full spectrum of dial. Between the static and pops of disc jockeys and jingles, Carmine turned to his mother and asked, "What did the doctor say was wrong with me?"

"Just a little bug," she said, the corners of her mouth jumping, "we'll get you some medicine and you'll be all better real soon."

The car crawled down main street before stopping in front of the drug store. Beth gathered up her purse and turned to her son. "You just wait here for me. It'll only take a minute."

She got out of the car and smoothed her dress before opening the pharmacy door. A bell chimed when she walked in the building. She walked past the black cushioned stools at the soda fountain and lightly ran her fingers over the edge of the bar. After nodding at the gangly boy replacing glasses, Beth approached the counter and stared at the collection of candy jars. "Oh, Beth! What can I do for you today?"

A woman in a pink uniform smiled at Beth as she approached the counter. "Hi, Gene. I just need to have this prescription filled. How are you doing," she said, digging into her purse and handing the woman a yellow slip of paper, "I'm sorry Baron and Carmine couldn't play longer yesterday. He's not feeling too good."

Gene smiled and took the slip from Beth. "I understand. Just hope he gets better soon so Baron will have someone to keep him company," she paused and examined the note, fidgeting with the edges of the paper, "let me go get this. Just a second."

As Gene left, Beth stared at the black and white tiled floor. "Gene," she started,"Baron hasn't said anything to you about Carmine, has he?"

"No. Just that he was feeling ill. Why? Is something wrong?"

Beth stared blankly and shook her head. She smiled, saying, "Oh, no. I was just wondering."

Gene smiled then went into the back room. Beth clasped her hands together and knotted her fingers. No one else knew. She let out a small sigh of relief as Gene returned with a white bag. "Here's his medicine. I'll just add it to your account. Tell Carmine I hope he feels better soon."

Beth thanked her, grabbed the bag, and quickly walked out of the store.

When they arrived home, Beth measured out a dose of medicine and tipped it into Carmine's open mouth. She handed him a glass of water and sat with him on his bed. A breeze came through the open window, blowing the tacked up pictures on the wall. Above Carmine's bed was a calender, a picture of the Lone Ranger, and a picture of the boy's father. Beth placed a hand on his ginger head and smoothed his sweaty hair. She touched his hot, freckled cheeks and smiled softly. "You need to get some rest, okay? Try and relax for a bit while I work in the yard. I'm right outside your window if you need anything."

As his mother walked through the house, Carmine could hear the floorboards creaking. He lay on top of the covers and looked out the window at the clouded sky. He dragged his nails against the wall behind his bed and turned his attention to the picture of his father. Before Carmine was two years old, his father died of pneumonia in the middle of January. The boy often wondered what things would have been like had his father lived. He thought his mother would be happier, less worn and impatient. She wouldn't have to work out in the yard in the heat or shampoo other women's hair at the beauty salon. Carmine wouldn't have to come home to an empty house after school and wait at the empty kitchen table.

He rose up to look over the window sill at his mother in the flower bed. Her skirt was gathered at her knees and brushed across the dark soil. Beth tossed aside handfuls of offending weeds and lightly touched the leaves and blossoms of the plants. She had her wilted brown hair tied up in a scarf, stray strands plastering themselves against her sweating forehead. Stopping occasionally to brush sweat off her forehead with her dress sleeve, she worked silently and intensely, never noticing Carmine watching her.

Beth raked the dirt through her fingers and thought of her husband. When she was pregnant, she would take care of the garden while her husband mowed the lawn and gathered pine cones and dead branches. He would fill up a wheelbarrow and guide it behind the house, throwing the brush into a large pile to eventually burn. Sometimes they would light the fire at night and watch the embers float into the dark sky. They ignored the heat and mosquitos and stare at the flames until the fire slowly died.

One day, her husband was tending to the bonfire in the backyard while Beth was planting day lilies. She had watched the heavy smoke from the pine needles snake above the house and stopped mid way through digging a hole. Turning her attention back to her work, Beth had stared at the fistful of dirt. It looked cool and dark and felt good in her bare hand. She brought the dirt up to her nose and smelled it; rich, strong and heady. Compulsively, her mouth had opened and she pushed the soil into her mouth. It was surprisingly moist and soft. It hadn't felt grainy or intrusive. She swallowed slowly and looked at her now empty hand. Just as she had gathered a second fistful, Beth was interrupted by a loud voice saying, "Are you eating dirt?!" Her husband had angrily grabbed her arm and continued to yell. "Why in the hell would you shovel dirt into your mouth? What are you thinking?!"

Beth felt a drop of water land on her bare arm. She looked at the gray sky and stood up, shaking the dirt off her skirt. On the porch, she wiped her feet off on the front mat and entered the house. "Carmine," she said, removing the scarf from her hair, "you better shut that window. It's raining."

Hearing no reply, Beth walked into Carmine's room. The room was empty and quiet. She walked across the room and opened the closet door, pushing aside the boy's hanging clothes, finding nothing. The rain outside came down in loud sheets. "Boy, you better stop fooling around," she said, stooping to look under the bed.

Slowly, Beth realized that Carmine was nowhere inside of the house. The curtains had all been pulled aside, doors hung open and the kitchen cupboards were all opened wide in pursuit. Her mouth twisted as she pushed open the screen door and stood on the porch. The sky had turned completely black and her calls for her son were drowned out by the rain.

Beth ran back inside and grabbed a flashlight from the cabinet full of cleaning products and old sponges. Her bare feet slapped against the bowing boards of the front porch as she ran down the front steps. Dropping to her knees, she turned on the flashlight and started to crawl under the house. The clay clung to her elbows as inched along, searching with the yellow shaft of light. "Carmine! You better get back inside right now!"

It smelled wet and musky under the house. There were no sounds of scraping or chewing; no wet swallows and no Carmine. Beth laid on the ground exasperated, smearing the red earth on her white dress. Tears ran down her face as she inched out from under the house and began running across the yard and down the muddy road.

"Carmine!"

Beth's feet slid and sunk into the mud on the road. She continued to yell the boy's name as her running threw the beam of her flashlight frantically. The rain beat hard against her shoulders as she headed to the river, a tight knot in her diaphragm of worry and guilt. She stood gasping for breath, legs splattered with mud and her wet hair plastered to her face. "Carmine!"

Beth thought of her son face down in a bed of mud, filled to the brim and blue. She approached the river in a panic. "Carmine!"

She surveyed the water and felt defeated. The muddy water had picked up speed, white capped and violent. Branches of trees and various debris rushed by, in and out of her periphery. Beth collapsed onto the bank, sobbing. If he had been here he would have surely been swept away by now. Taken miles down the river, or worse pulled under and held fast by rocks or dead trees.

In the distance, Beth could hear a high moan. She followed the sound, her flashlight revealing pieces of swaying trees and churning water. The light finally landed on the form of a young boy clinging onto a low lying branch off the bank. "Carmine!"

She ran forward, slipping on the bank and sliding up to her knees into the water. The current pushed Beth forward towards her son, threatening to tow her downstream. She gripped the muddy bank, dirt lodging itself under her fingernails. Clawing towards her son, Beth's knees barely breached the surface and her skirt stuck to the back of her thighs. She drew closer to the branch and began to see her son more clearly. He was shirtless and covered in mud. It was caked around his mouth and on his hands that gripped the creaking branch. Reaching him, she held fast to the limb and moved slowly towards him. "Carmine, take mama's hand and I'll pull you up on the bank, okay?"

The boy nodded, wide eyed. His muddy hand grasped at his mother's waiting hand. Grabbing onto her palm, his sticky hand squelched and their fingers interlocked. Beth pulled the boy forward, her feet sinking into the river mud, turning her legs into deep rooted pylons against the current. She grabbed him into her arms and started to slowly move her feet forward, bringing them to the shore. They collapsed onto the bank, intertwined and crying.

As she carried the boy back home, the rain slowing, Beth ran her hand over his mud caked hair. Her dress was stained with brown and red from the mud and clay. Carmine's pants were heavy with dirt, his arms wrapped around her neck and his head resting on her shoulder. "I'm not going to eat dirt anymore, mama," the boy said quietly.

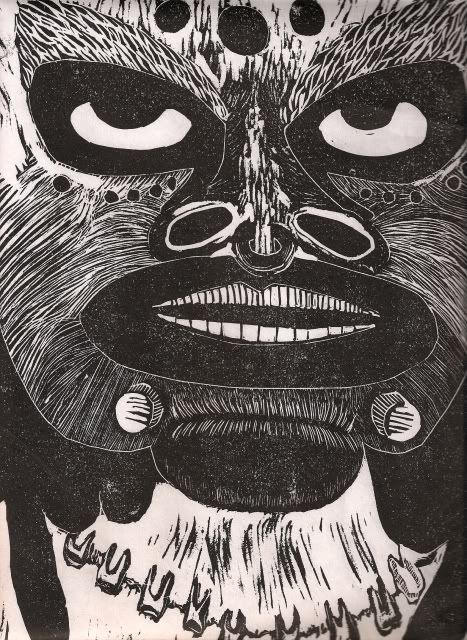

Beth shushed him as they approached the house, climbed up the steps and stood in the kitchen. Water dripped off of them, washing away the mud that gathered in a puddle on the floor. She didn't rush to clean it up. She didn't wipe off the boy's face. They silently stared at each other, two pairs of green eyes in masks made of earth.